- Home

- F. Paul Wilson

Double Threat Page 9

Double Threat Read online

Page 9

Another glance over her shoulder showed them closer, so she picked up speed. Maybe if she crossed the street …

As she veered leftward her foot caught on something and she fell forward with her hands flailing before her. She tumbled off the curb just as the road roller was reversing. Her left hand went under the drum and she screamed with pain like she’d never felt in her life.

4

Daley lay on her back and saw a blurry guy in a blurry white coat standing next to her. She blinked to clear her vision and expected to see Pard but, no, this guy had black skin. She saw now that he wore a white lab coat over green scrubs. He stood to her right; a scrub-garbed nurse adjusted an IV on her left.

“Stanka?” the nurse said. “Stanka?”

“Call me Daley.”

“Ah, you’re awake,” the black guy said. “That’s good. I’m—”

“Where am I?”

“Saint Michael’s Medical Center in Burbank.”

“I had a brain scan here yesterday.”

“Yes, I reviewed your records. I don’t know if you remember my name—you were quite distressed and in a lot of pain when I arrived—I’m Doctor Stabler. I’m a hand surgeon. You’re in the recovery room now.”

“Recovery? Hand surgeon? Why—?”

And then it all came rushing back. The fall, the road roller’s drum crushing her hand, the pain, the screams—hers and others—and then passing out. Coming to with the EMTs, the ambulance ride, the ER, injections that made her fuzzy, and now …

She tried to raise her gauze-swathed left arm but it wouldn’t move. She blinked for a better look at all that gauze and padding and—

“My hand!” Her left arm was too short. “What happened to my-my-my—?”

“We couldn’t save it,” Dr. Stabler said.

No-no! Couldn’t be! Had to be a bad dream, the worst nightmare ever!

He took her right hand in his. “My team and I tried our best but the injury was too severe. The bones were virtually pulverized, the vasculature torn, the little muscles that move your fingers were crushed and, well, partially cooked from the heat of the asphalt. We had to amputate.”

“You cut off my hand?” She could hear her voice escalating in tone and volume.

“I’m so sorry, Stanka—Daley. We did everything we could but it was simply impossible to save it.”

“But you had no right!”

The nurse said, “The possibility was explained before surgery and you signed the consent.”

“I don’t remember…”

“We had no choice, I’m afraid,” Stabler said. “If we’d left it attached it would have become necrotic and infected and threatened your life by spreading infection throughout your system.”

More details came back … She remembered falling, putting her hands out to keep from landing on her face, her left hand sinking into the fresh, hot asphalt and the roller going over it. Her scream made the operator slam the brake, but he stopped with the roller atop her hand. She was screaming Get it off! Get it off! when he jumped down to look, and his scream joined hers when he saw her. She’d passed out as he jumped back up to the controls.

My-hand-my-hand-my-hand-my-hand! Gone!

A scream rose to her lips but she bit it back. She did sob, though. Deep, wracking sobs from way, way down. She didn’t want to go through life with one hand. How was she ever going to manage that?

Dr. Stabler was rambling on about the wonderful things they were doing with prosthetics these days but she barely heard him. Her mind was numb to the future … a maimed, one-handed future.

They injected something into her IV line and the next thing she knew she was alone in a private room. No, not alone. A familiar figure stood close by the bed.

Pard.

(“I’m so sorry this happened, Daley.”)

“Pard … you’re still around.”

A grim smile. (“I am with you always. But this is all my fault.”)

She stared at the foreshortened end of her mummy-wrapped left arm for a long moment. “I still can’t believe it happened.”

(“I take full responsibility.”)

“I’m perfectly glad to blame you, but how do you figure that?”

(“Pure hubris on my part. I healed that woman and then goaded you into bragging about it on my behalf.”)

“‘Bragging’?”

(“Absolutely. I could have simply done my work and then just let her discover she’d been healed. But I pushed you into announcing it.”)

“I sort of got into it. Remember ‘magic fingers’?”

She remembered waggling her ten fingers in the air … and a lump formed in her throat as she realized she’d never do that again.

(“Still … I prompted you.”)

“I don’t get it.” She pointed to where her hand used to be. “What’s all that got to do with this?”

(“Don’t you see? Doctor Holikova and those others associated you with the cures, and the lung-tumor lady wanted you to help all her sick friends. They never would have been chasing you if I’d just told you to keep the cures between us.”)

He had a point … sort of.

“All right, maybe you are to blame in a roundabout way, but there’s no way you could have known this would happen.”

She smacked her lips. Thirsty. She pointed to the water pitcher on the nightstand.

“Pour me a glass of water, will you?”

Pard gave her a dubious look, then went to grab the pitcher. His hand passed right through it.

(“Have you forgotten that I’m just an image in your brain?”)

Well, damn, she had forgotten. He looked so solid. Showed how real Pard had become to her. And how useless he was. Worse than useless—she’d lost her hand because of him!

She didn’t know if it was the drugs they were feeding her or what. Maybe it was just … everything, but suddenly she felt helpless, trapped in a life that seemed hopeless and awful. She began to sob.

“What good are you? I mean, really? You’ve done nothing but mess up my life. Three days ago I was happy and I was whole! Now look at me! Three days! That’s all it took you to totally fuck up my life! I wish I’d never gone into that cave, or maybe I wish I’d fucking died in there! Anything’s better than this. Why don’t you just die and leave me in peace!”

Talking only worsened her thirst. She’d have to buzz for the nurse. But she’d close her eyes first … just for a few seconds …

As she faded away she heard Pard say, (“I’m going to make this up to you, Daley. I’ll make this right, I swear…”)

5

“Ungh.”

Cadoc’s gray, papery hand appeared and slid his queen two diagonal spaces. Then he tapped a finger once on Rhys’s king, the signal for “check.”

Rhys hadn’t seen that coming. As he studied the board he realized he needed to pay closer attention. Forget the distractions of the day and focus on the game.

He enjoyed his regular Saturday night chess game with his older brother, although the conditions could get off-putting at times. Cadoc insisted they play in his heavily curtained suite at the rear of the Lodge, and that the light in the room be limited to one small gooseneck lamp with a high-intensity bulb sharply focused on the board. As a result the board seemed to float in empty blackness.

Rhys went along with his brother’s obsessive privacy about his appearance. No mystery as to why the guy did not want anyone looking at him. He’d been less guarded as a child and Rhys had become familiar and even comfortable with Cadoc’s papery gray skin. His voice hadn’t been affected yet and he spoke normally, but as time went on, Cadoc’s condition became worse, wrecking his voice, and he grew less and less comfortable with his appearance until he adopted a lifestyle of keeping himself locked away in the daylight hours and venturing out only after everyone else had turned in.

Okay, it came down to more than just papery skin. Every member of the Pendry Clan—all five families—had a patch of rough gray skin somewhere on his or

her body. The Pendry Patch. Some were large, some were small, but no one on record had the Patch to Cadoc’s extent. The poor guy looked like a cross between a paper wasp nest and a peeling river birch.

Rhys forced his attention back to the board, littered as usual with gray flakes of Cadoc’s skin. You could always tell where Cadoc had spent some time. Rhys spotted an easy escape from check and took it.

Cadoc didn’t hesitate. He moved his queen again and tapped Rhys’s king twice.

“Ungh.”

Two taps … checkmate.

“Rats! You knew I’d fall for that!”

Rhys looked for a way out but found none. When Cadoc said ’mate, he meant it. He leaned back.

“Hey, sorry I didn’t give you a better game, Cad,” he said, rubbing his eyes. “My mind’s all over the place tonight.”

A sheet from Cadoc’s ever-present notepad dropped onto the chessboard.

Papa?

Cadoc always referred to Dad as Papa.

“Yeah, well, who else? He’s become obsessed with this ‘pairing’ message and the ‘Duad’ he found in the Scrolls. But will he let me have a peek at his off-limits sections? Nooooo.”

The faint sounds of a pencil scribbling, then another sheet dropped on the board.

Papa is quite mad, you know

“‘Mad’ as in pissed off or crazy?”

Crazy

Rhys laughed. “Yeah. Crazy like a fox. Speaking of Dad, where is he?”

At regular intervals—usually before a Nofio—he’d disappear late at night. Rhys would hear him go out and come back a few hours later.

Out

“I know that. Where out?”

Desert

“What’s he do there?”

His business

“You don’t know?”

Cadoc tapped the His business note. Rhys figured if his brother knew, he wasn’t going to say. He switched to another line of inquiry.

“Dad was telling me how he let you see some of the undigitized Scrolls and how you found something about this Duad thing.”

“Ungh.”

One grunt: a yes.

“Anything interesting? Anything I should know?”

Vague

“Yeah, that’s what Dad said. That vagueness is what’s driving him nuts. And he’s taking me with him.”

Seen all translations

“Who? You? Even the sections he’s encrypted?”

All

“He told me he wasn’t going to show you, damn it.”

Doesn’t know

Cadoc must have accessed them during one of his late-night rambles through the Lodge.

“Wh-what do they say? What’s he keeping from me?”

Bad stuff

Crazy stuff

Awful stuff

“What, damn it!”

no tell

“C’mon. You can tell your best bro.”

Can’t tell

Trouble

“Dad will never know, so—”

It’s Sat night. Should be out

with Fflur, not babysitting me

“Don’t try to change the subject.”

Cadoc’s hand shot out and gave the last note two insistent taps. Respond.

Fflur … Flur Mostyn, the girl the clan Elders had chosen for Rhys to marry. A nice enough girl, not bad looking. Everyone said they’d make a fine couple. They were scheduled to be married when he turned thirty—everything happened after he turned thirty. But he was in no hurry for the wedding. Something was missing between him and Fflur. He wanted sparks. Was that too much to ask? Or were sparks something that happened only in books and movies?

“I’m not babysitting, Cad. I’m playing chess with my only brother. I can always go out.”

I’ll be out later

“Where? Up on the roof?”

Out and about

I roam

Rhys blinked. “You mean … out and about down in town?”

All over—solar & wind farms & trailers

“Oh, crap. You could be seen. I know you don’t want that.”

Very careful

“But what do you do out there in the dark?”

Watch & see things

Listen & hear things

“Like what?”

I know things

“C’mon, bro. Like what?”

Someday I tell

Was Cadoc doing a Peeping Tom thing down there in Nespodee Springs? Getting caught would be devastating for him. They’d treat him like a freak, make a spectacle of him, everything he wanted to avoid.

“I can’t tell you what to do, bro, but you’re courting disaster out there.”

I know

Risk = life

Jesus. Most people would say life equaled risk. Rhys sensed his brother meant what he wrote.

“Please be careful.”

Only no moon or new moon

“Still…”

Thanks for game, Rhys

“You don’t want a rematch?”

Done tonight

“Okay, then. Might as well turn in. I’ve got lifeguarding the Nofio to look forward to tomorrow.”

Fuck the nofio

“Whoa. Where’s that coming from?”

forget it

“No, seriously. What’s the issue?

so much you don’t know

“Enlighten me then.”

you learn soon enough

Rhys was getting really sick of hearing that. He rose and gathered up the note sheets. He wanted to keep these.

Cadoc blew his flakes off the board, then rapped on the table and held out his hand.

“I’ll chuck these out for you.” A lie, but …

Another pair of knuckle raps. Give.

“All right, all right.”

He handed them over then headed for the door. “But remember what I said about being careful.”

“Ungh.”

As Rhys closed the door behind him he heard the note sheets ripping. He stood in the hall, thinking about one of Cadoc’s notes: Bad stuff / Crazy stuff / Awful stuff

How much of that could he believe?

SUNDAY—FEBRUARY 22

1

Daley was suddenly wide awake.

A voice was saying, (“Time to get out of here.”)

She looked around. Here? Where…?

Oh, yeah. The hospital room … because of her hand …

… we had to amputate …

Oh, God, her hand … her hand was gone! How could she have forgotten? Then again, they’d been pumping morphine into her all night.

Pard stood by the bed. (“Daley, get up and get dressed. We need to leave.”)

Daylight seeped between the blinds. Morning already?

“Leave? What are you talking about?”

(“We can’t let them see your hand. They’ll be serving breakfast soon and then that Doctor Stabler will be in to check on your stump.”)

“Yeah, well, that’s his job.”

(“Yes, but you no longer have a stump.”)

Did he just say—?

“What?”

(“I spent the night growing you a new hand.”)

She levered up in bed and raised her arm. “What?”

(“Be careful with that. The muscles are rudimentary and stretched out, and the bones are nowhere near fully calcified yet, so it’ll be weak and fragile for a while.”)

She stared at the end of her mummy-wrapped left forearm. Last night it had looked horrifically, sickeningly shortened … abbreviated. Now something was stretching out the gauze at the end where her hand should be … used to be …

… was again?

She wiggled her fingers and saw movement under the gauze.

Oh, God, my hand—my hand!

Okay, calm down.

She’d thought yesterday was a bad dream, and now today she had to be having another dream, a good dream, but an impossible dream, because, well, she knew crabs could grow a new claw and lizards could grow a new tail,

but humans simply couldn’t grow a new hand. They just couldn’t. So this was another dream, a wish-fulfillment dream that—

(“Daley, please! We’ve got to go. I should have thought of this last night but you were so upset and I was so anxious to make this right for you that I overlooked the fallout that would ensue if it was discovered.”) Pard was moving back and forth between the bed and the closet like a dog who had to go out. (“Please move. I’d bring your clothes out to you but I can’t.”)

“What’s the big hurry?”

(“You can’t let the staff see what I’ve done. How will you explain it?”)

“Did you really do it?” Could this be true … she had a left hand again? She reached for the gauze. “I want to see.”

(“No-no-no! Leave the gauze alone. I rearranged it to hide what I did.”)

“But—”

(“You have the rest of the day to admire my handiwork, but if you don’t leave right now, you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.”)

“Isn’t that a bit of an overstatement?”

(“You like your alone time? How much alone time do you think you’ll have when you’re known as the only person in human history ever to regenerate a limb?”)

The truth of that struck like a blow. He was right. She had a vision of herself on the cover of the National Enquirer.

“Oh, shit! Shit-shit-shit!”

She threw back the sheet and began to slide off the mattress when she noticed the IV tube running into her left arm.

“What do I do about that?”

(“I emptied it during the night because I needed the glucose. Pull it out.”)

“Just like that?”

(“It’ll bleed some but that’s the least of your worries right now.”)

She loosened the tape and gauze pad over the insertion site and pulled out the needle. A little clear fluid dribbled from the tip, and blood leaked from the hole in her skin. She pressed the gauze over it and rushed to the closet where she found her shoes and jeans, her cap, and her somewhat ruined blouse—whoever had removed it had slit the left sleeve first.

Dressing with one hand wasn’t easy but she managed. After retrieving her phone and ID folder from the nightstand, she was ready to roll.

“Now what?”

(“Now we improvise. First thing we do is get the lay of the land—or, in this case, the hallway.”)

Crisscross

Crisscross Ground Zero

Ground Zero Short Stories

Short Stories The Select

The Select Codename

Codename Bloodline

Bloodline A Soft Barren Aftershock

A Soft Barren Aftershock The Tomb

The Tomb The Complete LaNague

The Complete LaNague The Tery

The Tery Dark City

Dark City Deep as the Marrow

Deep as the Marrow The Fifth Harmonic

The Fifth Harmonic Conspiracies

Conspiracies Fear City

Fear City Wheels Within Wheels

Wheels Within Wheels Wayward Pines

Wayward Pines The Portero Method

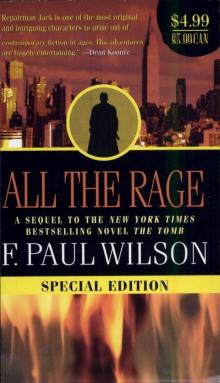

The Portero Method All the Rage

All the Rage Infernal

Infernal The Barrens & Others

The Barrens & Others The Keep

The Keep Quick Fixes: Tales of Repairman Jack

Quick Fixes: Tales of Repairman Jack Virgin

Virgin Hosts

Hosts Dydeetown World

Dydeetown World Midnight Mass

Midnight Mass Black Wind

Black Wind The Christmas Thingy

The Christmas Thingy The Last Rakosh

The Last Rakosh The Last Christmas: A Repairman Jack Novel

The Last Christmas: A Repairman Jack Novel SIMS

SIMS Thy Brother's Keeper

Thy Brother's Keeper Panacea

Panacea The Touch

The Touch Scenes from the Secret History

Scenes from the Secret History Scenes From the Secret History (The Secret History of the World)

Scenes From the Secret History (The Secret History of the World) Implant

Implant The Dark at the End

The Dark at the End Fatal Error

Fatal Error Wardenclyffe

Wardenclyffe Sibs

Sibs The God Gene

The God Gene The Void Protocol

The Void Protocol Artifact

Artifact The Compendium of Srem

The Compendium of Srem Legacies

Legacies Reprisal

Reprisal Jack: Secret Vengeance

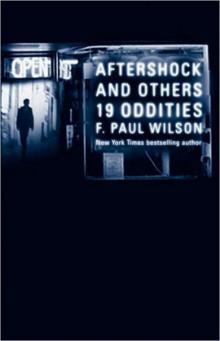

Jack: Secret Vengeance Aftershock & Others: 19 Oddities

Aftershock & Others: 19 Oddities By the Sword

By the Sword Interlude at Duane's (Thriller: Stories to Keep You Up All Night)

Interlude at Duane's (Thriller: Stories to Keep You Up All Night) Fatal Error rj-13

Fatal Error rj-13 Crisscross rj-8

Crisscross rj-8 Codename: Chandler: Fix (Kindle Worlds Novella)

Codename: Chandler: Fix (Kindle Worlds Novella) Dydeetown World lf-4

Dydeetown World lf-4 Signalz

Signalz Codename_Chandler_Fix

Codename_Chandler_Fix The Dark at the End (Repairman Jack)

The Dark at the End (Repairman Jack) The Complete Adversary Cycle: The Keep, the Tomb, the Touch, Reborn, Reprisal, Nightworld (Adversary Cycle/Repairman Jack)

The Complete Adversary Cycle: The Keep, the Tomb, the Touch, Reborn, Reprisal, Nightworld (Adversary Cycle/Repairman Jack) Repairman Jack 03 - Conspiracies

Repairman Jack 03 - Conspiracies Ground Zero rj-13

Ground Zero rj-13 Repairman Jack 02 - Legacies

Repairman Jack 02 - Legacies The Dark at the End rj-15

The Dark at the End rj-15![Repairman Jack [02]-Legacies Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/21/repairman_jack_02-legacies_preview.jpg) Repairman Jack [02]-Legacies

Repairman Jack [02]-Legacies Double Threat

Double Threat The Tery lf-5

The Tery lf-5 The God Gene: A Novel

The God Gene: A Novel Wayward Pines: The Widow Lindley (Kindle Worlds Novella)

Wayward Pines: The Widow Lindley (Kindle Worlds Novella) Reborn ac-4

Reborn ac-4 Reprisal ac-5

Reprisal ac-5 New Title 1

New Title 1 Healer lf-3

Healer lf-3 An Enemy of the State lf-1

An Enemy of the State lf-1 Interlude at Duane's

Interlude at Duane's By the Sword rj-12

By the Sword rj-12 Hardbingers rj-10

Hardbingers rj-10 Wheels Within Wheels lf-2

Wheels Within Wheels lf-2 Jack: Secret Circles

Jack: Secret Circles Nightworld ac-6

Nightworld ac-6 Quick Fixes - tales of Repairman Jack

Quick Fixes - tales of Repairman Jack Secret Circles yrj-2

Secret Circles yrj-2 Jack: Secret Histories

Jack: Secret Histories Haunted Air rj-6

Haunted Air rj-6 An Enemy of the State - a novel of the LaNague Federation (The LaNague Federation Series)

An Enemy of the State - a novel of the LaNague Federation (The LaNague Federation Series) Repairman Jack 05 - Hosts

Repairman Jack 05 - Hosts Cold City (Repairman Jack - the Early Years Trilogy)

Cold City (Repairman Jack - the Early Years Trilogy) The Peabody-Ozymandias Traveling Circus & Oddity Emporium

The Peabody-Ozymandias Traveling Circus & Oddity Emporium Uncommon Assassins

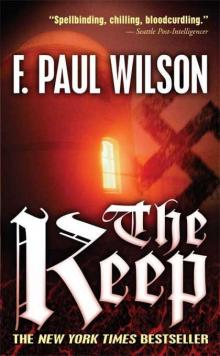

Uncommon Assassins Adversary Cycle 01 - The Keep

Adversary Cycle 01 - The Keep Repairman Jack 06 - The Haunted Air

Repairman Jack 06 - The Haunted Air Bloodline rj-11

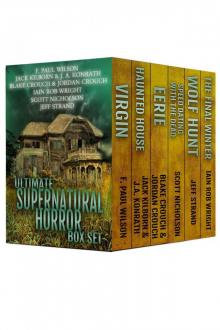

Bloodline rj-11 Ultimate Supernatural Horror Box Set

Ultimate Supernatural Horror Box Set The Keep ac-1

The Keep ac-1 Repairman Jack 04 - All the Rage

Repairman Jack 04 - All the Rage Aftershock & Others

Aftershock & Others All the Rage rj-4

All the Rage rj-4 Nightworld (Adversary Cycle/Repairman Jack)

Nightworld (Adversary Cycle/Repairman Jack) Conspircaies rj-3

Conspircaies rj-3 Hosts rj-5

Hosts rj-5 Infernal rj-9

Infernal rj-9 The God Gene: A Novel (The ICE Sequence)

The God Gene: A Novel (The ICE Sequence) Secret Histories yrj-1

Secret Histories yrj-1